CHARLESTON, S.C. — Faint yellow with a blue screened-in entrance, the home on Cypress Road is squeezed in among the many others, simple to overlook in the event you’re driving previous. The roof is adorned with uncovered rafters beneath the eaves. A blotch of grass buffers a brief, black, chainlink fence from the road. Issues are usually quiet inside, aside from the chatter of daytime TV or an occasional developer knocking on the entrance door, attempting to purchase the place.

The seems to be taking pictures round the lounge early final month weren’t accusatory, however cautious. Possibly confused. Jackie White and her mom, Mary Lee Rhodes, had recognized a stranger was coming down to go to, however by no means might work out what any of this was about. Again after we’d first spoken, a number of weeks earlier, they hung up the landline, checked out one another and questioned why, in any case these years, anybody needed to know.

Ronnie Gadsden launched everybody. An outdated coach, one used to creating connections, he made positive Jackie and Mary Lee have been snug with the customer on the sofa. Then he pulled over a chair, positioned himself to the facet and sat down. He needed to listen to this for himself.

That’s when Jackie eliminated her glasses, positioned them atop her head, gave a smile that invited a hug and requested the stranger to remind her how all this got here to be.

“All proper, so there’s this webpage on the web …”

MaxPreps.com is a longtime chronicler of highschool sports activities, one providing rankings, recruiting headlines and highlights of no matter LeBron James’ son is doing at any given time. Down within the website’s archives, previous the volleyball All-America lists and the 8-man soccer nationwide rankings, are a great deal of historic pages chronicling everybody from American icons to the nameless names of highschool sports activities. That’s the place you will discover an assembled file guide of the best single-season scoring averages in boys highschool basketball historical past.

Begin scrolling and also you fall into the web page. A gorge filled with all kinds of names from all possible locations. Every one a narrative. Bennie Fuller (No. 5, 50.9 ppg) as soon as scored 102 factors in a single recreation for Arkansas College for the Deaf in 1971, then performed at Pensacola (Fla.) Junior School, then labored for the U.S. Postal Service. Bjorn Broman (No. 9, 49.4 ppg), a latest Minnesota highschool legend, reached the 2017 NCAA Match at Winthrop and is now a TikTok creator with 1.4 million followers. Truitt Weldon (No. 23, 45.0 ppg) was raised in a strict non secular dwelling in Sabine Parish, La., and mocked for enjoying highschool video games in blue denims.

You discover school coaches. Present professionals. A former Congressman. Wilt Chamberlain. Trae Younger. You discover Mickey Crowe, the Wisconsin schoolboy cult hero who witnessed John W. Hinckley Jr.’s assassination try on President Reagan and was the topic of a 2013 biography titled “Over and Again.”

You get misplaced for hours. One identify after one other. Information have been compiled by Kevin Askeland, a 59-year-old math instructor from Yuba Metropolis, Calif. The self-described highschool sports activities historian says he exhausted all out there assets of the Nationwide Federation of State Excessive College Associations file books, scanning all 50 state file books. He ended up with a listing of 112 names. Every is a rabbit gap, one that ought to take you someplace.

Aside from the No. 1 identify on the listing.

55.6 ppg — Finnell White, Lowcountry Academy (Charleston, S.C.), 1987-88

Up comes Google. In goes the identify.

F-I-N-N-E-L-L W-H-I-T-E

The search outcomes land like a discarded scratch-off ticket. The one different point out of White’s identify comes from the “Faces within the Crowd” part of a March 1988 Sports activities Illustrated. Kirk Gibson was on the duvet that week, sporting Dodger blue. The blurb reads: “Finnell, a senior guard, scored 79 factors, made a 64-foot three-pointer to finish the primary half and a game-winning three-pointer with :06 left as Lowcountry Academy beat Andrews Academy 90-89.”

That’s it. No wiki web page, no hyperlink to a Corridor of Fame induction, not even a hyperlink to an outdated story or two. No obituary.

How can this presumably be? Such empty outcomes are an affront to our info-wired world. If 55.6 factors is certainly the best common ever by an American prep participant, how do we all know nothing in any respect about Finnell White of Lowcountry Academy? How does somebody with such a mark vanish in time?

And why, extra importantly, is there a gravestone a number of miles from right here, over in Sundown Memorial Gardens, for Finell Demetrios White, the place the identify, apparently misspelled in all places else, is etched accurately F-I-N-E-L-L?

Listening to all this, Jackie White, now 75, nodded and smiled, alongside for the journey, attempting to get her fingers round all this. She traded glances along with her mother. Ms. Rhodes, 93, suffered a latest stroke however continues to be sturdy sufficient to stroll to the nook retailer. She narrowed her eyes and nodded her head.

Then they started.

Jackie White knew what was occurring each on the within and the surface. A single mother of two, she labored at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, a maximum-security jail for girls simply north of New York Metropolis. She clocked shifts within the mailroom in search of contraband, shifts on the ground monitoring gen pop, shifts overseeing the chow corridor. Her philosophy on inmate care: “If you happen to act proper, I deal with you proper. If you happen to act a idiot, me and also you gonna idiot collectively.”

It was the mid-80s in East Harlem and Jackie’s guidelines carried over to dwelling. Elevating her boys on Madison Avenue and East one hundred and thirty fifth Road, she ran a decent ship and infrequently supplied sage recommendation for the streets. By no means maintain a package deal somebody fingers you. Don’t stroll round in your good sneakers; maintain ’em in your backpack till you get the place you’re going. Finell, the oldest, and his brother, Daryl, principally listened, however finally different forces began taking on.

Finell grew up taking part in at Rucker Park, the streetball mecca a couple of mile and a half from the household’s condo. If he wasn’t there, he was on any of the opposite courts dotting the world. He ran in video games blended among the many characters of the parks. Previous guys, younger guys. Guys there to play. Guys there to combat. Guys who performed in highschool, perhaps even school. Guys who’d by no means worn an actual jersey, however have been ok for any group, anyplace. Finell was a bit lefty guard. Sturdy, thick, fast, and intelligent. He realized the sport the best way he noticed it. Creativeness, improvisation, aggression.

However that wasn’t his solely curiosity. “Helluva card participant, that one,” Jackie laughs, head shaking, fingers within the air.

Finell didn’t merely play the occasional card recreation. He began playing in elementary college, emptying youngsters’ pockets earlier than lunch break. When he went to Julia Richman Excessive on the Higher East Aspect, what some native police known as “Julia Rikers,” he’d maintain courtroom within the cafeteria, dealing hand after hand. That’s, when he really went to highschool. Most of the time, Jackie caught him skipping class, out doing God is aware of what. By the point Finell was 15, she was not frightened about him getting arrested, however anticipating it.

“And that’s after I was like, nah, he’s received to go,” Jackie remembers. “I advised him, ‘It’s time to go down South.’”

Jackie Rhodes was born in South Carolina. She had moved from Charleston to New York greater than a decade earlier, again in 1967, arriving in a metropolis burning with civil unrest. She was 18, on her personal, and hoping to enroll in medical commerce college. Inside a yr she was pregnant with Finell. Having cut up along with his father, James White, in 1971, Jackie started making common treks all the way down to Charleston each summer time, the place her mom might assist elevating the boy. As a toddler, Finell referred to as his grandma “Mae Mae.”

Now 16, Finell was shifting to Charleston to dwell full-time. He was the kind of child to get together with anybody, speak to anybody. Quick, humorous. Even when he received in hassle, it was arduous to be mad at him, not to mention keep mad at him. Heading south, he was about to expertise life as an outsider. Slower, stricter, smaller. He rode within the passenger seat of Jackie’s burgundy Toyota Corolla alongside 700 miles of Jap seaboard, by Philadelphia, by Washington, D.C., previous Norfolk, Va., by North Carolina, all the way down to the South Carolina shoreline. Jackie dropped him off on Cypress Road and drove 700 miles again.

“I advised him, ‘This ain’t like New York, now,’” Jackie says. “You’re a squirrel of their world down there.”

Mae Mae lived in North Charleston, the place the native public college, Burke Excessive, had a booming enrollment of over 1,700 college students and a pair of boys 4A state basketball titles in 1976 and 1984. It additionally had its points.

“We have been form of the difficulty college,” says Jamar Washington, a Burke participant on the time. “It was a giant college with totally different guys from totally different areas, totally different tasks, totally different hoods, all going to at least one college. Fights, all the time. East facet, west facet. Rival gangs. All that.”

Mae Mae wasn’t about to ship Finell to Burke. As an alternative, she discovered a tiny, undersung college out on the perimeters of Charleston, close to the outdated Middleton Place plantation. Lowcountry Academy was precisely what she needed — small, non-public and deeply unserious about basketball. The varsity’s headmaster, Samm McConnell, as soon as advised a Columbia, S.C., newspaper that “the smallness of the place has been conducive to protecting folks in class.” Excellent.

The Lowcountry basketball group was coached by a person named Howie Comen, a neighborhood non-public eye whom McConnell initially enlisted to analyze what he suspected was attainable dope smoking behind the college. Comen didn’t uncover narcotics, however did uncover a scholar physique with nothing to do after lessons. Comen advised McConnell that the youngsters wanted to play sports activities. McConnell responded by hiring Comen as the college’s athletic director, basketball coach and political science instructor. That’s how the Lowcountry Wildcats have been born.

“I didn’t precisely know a lot,” says Comen, whose solely prior basketball expertise, he explains, was taking part in in a synagogue league as a child. “We have been fairly dismal, to be sincere.”

The 1985-86 season was powerful. A 1-9 file. In a college with about 120 college students from kindergarten by twelfth grade, Comen didn’t have sufficient younger males to area a highschool boys group or sufficient younger girls to area a women group. So Lowcountry was considered one of solely a handful of excessive colleges within the nation with a co-ed varsity basketball group. The dearth of a house health club was arguably a bigger difficulty.

This was this system Finell White, straight from Harlem, walked into within the fall of 1986.

From a distance, at 5 ft 11, he seemed like every other child. Up shut, he seemed like a person. Wise mustache. Shoulders like hubcaps. Mellow eyes that had seen some issues. Taking part in a schedule of small, rural, virtually completely White non-public colleges, the 17-year-old was instantly, and comically, the best participant the South Carolina Impartial College Affiliation (SCISA) had ever seen. He averaged 34.7 factors per recreation in his first season, main Lowcountry to a 9-5 file. His grade degree wasn’t completely clear, however nobody appeared to thoughts.

“He was phenomenal,” Comen says. “However the perfect half was that he didn’t come off like a badass. He wasn’t Mr. Basketball. He had this demeanor that everybody was drawn to. I believe he appreciated attending to be a child.”

Comen stepped apart after the 1986-87 season, handing the Lowcountry group over to assistant coach Ronnie Gadsden. He, in flip, got down to enhance the Wildcats’ schedule and unfold phrase of the group’s star. The 1987-88 season started with Finell scoring 50 within the opener in opposition to St. John’s, 59 in opposition to St. Stephen, 60 in opposition to Lord Berkeley. The joke amongst SCISA officers was that Finell averaged 12 steals a recreation, however eight have been from his teammates.

None of this sat significantly nicely with Finell’s buddies in North Charleston. Nobody might perceive why one of many metropolis’s greatest ballers was taking part in out within the sticks, destroying 5-foot-5 15-year-olds. Everybody at Burke Excessive knew Finell from pickup video games in neighborhood parks. They knew he grew up taking part in at Rucker. They needed desperately for him to affix them on the college group.

“We’d have been unstoppable,” Washington says. “He got here with a talent set we’d by no means seen earlier than. Nobody dealt with the ball like him. Nobody. The jumper was kinda suspect, however, hell, he might get to the outlet each time he needed, in order that didn’t matter.”

Finell’s scoring totals, fantastical figures tallied in obscure video games, grew increasingly absurd. Oronde Gadsden (no relation to Ronnie), a future six-year NFL broad receiver with the Miami Dolphins, lived on the identical block and counted Finell amongst his buddies. A two-sport star at Burke, Gadsden would race dwelling on Friday nights to look at the ten o’clock information.

“Needed to see if our recreation made the highlights,” Gadsden says, “and what number of factors Finell scored.”

Gaudy numbers are how some names come to drop into and out of historical past, and the way traces start to blur between delusion and actuality, legend and lore. In February 1988, Lowcountry traveled to Andrews Academy, an impartial college about an hour outdoors Charleston. Strolling in, the Wildcats, based on Ronnie Gadsden, heard a voice yell out, “N— aren’t allowed on this health club.” Finell, considered one of 4 Black gamers on the group, and Gadsden, the one Black coach within the SCISA, seethed.

Finell responded by scoring 79 of Lowcounry’s 90 factors. In the long run, launching a 3-pointer along with his group down two and 6 seconds remaining, the 18-year-old turned to the Andrews bench, stored his follow-through excessive within the air and yelled, “Sport!” Not less than, that’s how the story goes.

Gadsden raced to name the newspapers. The Night Submit. The Information and Courier. The State. Not solely had Finell scored 79 factors, but in addition had achieved so along with his group lacking 4 — 4! — starters. Two missed the bus to the sport, one was out with the flu, and one other fouled out within the first half. The truth that the sport was performed on a rubber flooring in entrance of perhaps 50 folks? That didn’t significantly matter. The story quickly unfold nationally, syndicated in papers throughout the nation. Sports activities Illustrated printed Finell’s headshot amongst its “Faces within the Crowd” within the March 7, 1988 difficulty, a smile so assured you understand he flashed it after each a type of 79 factors.

Showing in SI, on the time, was equal to a moon touchdown. Points have been handed round Lowcountry, handed about Burke, and handed round Julia Richman, up in New York.

Finell adopted his 79-point recreation with a 71-point outing in opposition to Nation Day College. Then 56 in opposition to Archibald Rutledge Academy. Then 48 in opposition to Sea Island Academy.

All of the anticipated scenes of a schoolboy fever dream adopted. Finell was featured in these native papers, named to native all-star groups and rumored to be getting recruited by main schools close to and much. But, in all places he drew reward, his first identify was misspelled. An additional N. Nobody ever bothered to appropriate anybody. To today, Jackie remembers as soon as asking her son why. He answered, “Oh, Mommy, they know who it’s.”

There are disconnects required for threads of historical past to return quick, failing to achieve from then to now. For Finell, it wasn’t his identify. Hell, at present, in the event you search it accurately, you provide you with fewer outcomes than the wrong model.

No, on this case, the disconnect comes through an abrupt finish of occasions.

These rumors of Finell being a big-time school recruit? They don’t significantly maintain up. Neither Cliff Ellis, the Clemson head coach on the time, nor George Felton, the South Carolina head coach, can recall his identify. Tubby Smith, considered one of Felton’s assistants, says with a touch of unhappy uncertainty, “I bear in mind the identify, nevertheless it’s arduous to image him,” earlier than asking, sincerely, “Did we recruit him?”

Finell’s brother, Daryl, is satisfied North Carolina was an actual risk, saying, “I don’t know why that didn’t occur. Possibly grades or no matter.” Jim Boeheim, who a neighborhood Charleston paper reported had invited Finell to a 1988 spring break go to, based mostly on “sources” round Finell, at present can’t recall pursuing anybody by the identify of Finell White.

Different in-state school coaches, Butch Estes (Furman), Randy Nesbit (Citadel) and even John Kresse, the legendary School of Charleston coach, who labored solely 2 miles from Cypress Road, all draw blanks.

See, like in life, this story cooperates much less the longer it goes. Of all of the twists, it seems Finell completed the 1988 college yr a number of credit in need of graduating and needed to full them at, of all locations, Burke Excessive. Within the film model of this story, he would’ve lastly performed alongside Jamar Washington, Oronde Gadsden and the remainder of the fellows from North Charleston, and exploded into the star recruit he might have been. On this model, he was as a substitute dominated ineligible to play, ending his highschool profession. Relying on whom you ask, it was both the college’s resolution, or the coach’s resolution, or a highschool athletic affiliation ruling. Both approach, it’s unattainable to not surprise what-if.

“If he had an opportunity to play at Burke,” says Ronnie Gadsden, “I believe he would have proven all these folks that he was the true deal.”

After sitting out the yr and ending highschool within the spring of 1989, Finell in the end thought of presents to play basketball at Morgan State, North Carolina A&T, Anderson (S.C.) Junior School and Benedict School. He selected Benedict, an NAIA traditionally Black school in close by Columbia, S.C., however lasted just one season. Story goes that, as a 20-year-old freshman, Finell didn’t get on with the coach, however who is aware of? Neither the college nor the NAIA have any statistical information from that 1989-90 season. Newspaper clippings dug up within the Charleston Public Library say he commonly got here off the bench to attain 10 or 12 or 14 factors.

And that was it.

Finell was achieved. He packed his issues after one season at Benedict, gave Mae Mae a hug and set off again to New York, abandoning a reputation that lingered, then light, and the query that persists anytime a narrative leaves you feeling empty afterward. What occurred?

In June 1994, Houston Chronicle author George Flynn traveled to Third Road in New York, to the legendary blacktop often called “The Cage,” for a narrative thought. Flynn needed to satisfy the “street-hoop corridor of famers” who have been on the courts that day to preview an upcoming NBA Finals matchup between the Knicks and the Rockets. Mario Elie and Kenny Smith, two members of the Rockets, had each performed at The Cage years prior.

One after the other, Flynn described the gamers on the park that day. Finell White (spelled accurately), age 24, was “glistening with recreation sweat,” he wrote. Flynn shared Finell’s ideas on the sequence — that Hakeem Olajuwon wanted to go to his left, that Charles Smith wanted to focus, and that Vernon Maxwell was taking too many jumpers.

It was a coincidence Finell was at The Cage to be interviewed that day as a result of, within the mid-90s, he might have been at any courtroom, anyplace, at any time. “Brooklyn sooner or later, Queens one other,” says Daryl Smith, 46. “It didn’t matter. He simply needed to play different nice gamers.” It’s stated Finell dueled with Felipe Lopez in some all-time bangers. It’s stated that he practically landed a spot in a type of outdated Spirit streetball commercials. It’s stated he carried the cachet of being a recognized participant on any courtroom he stepped upon.

Finell White grew as much as be one of many guys he grew up taking part in in opposition to.

“Folks would all the time ask him, like, ‘How are you not within the league?’” Daryl White says.

It was a sophisticated query. In his early 20s, Finell thought one other school may come round sooner or later, however the cellphone by no means rang. He stayed in form, his brother says, considering there could be a tryout someplace, someday. At one level, he tried out for an area league soccer group. “Nearly made it, I believe,” Daryl says. He thought of touring abroad, in search of a professional basketball contract, however, as Jackie places it, didn’t know methods to go about such issues.

“Tried to make the perfect of it,” Jackie says slowly, considering of all the possibilities they thought may come and of all the boundaries that proved in any other case. “He had plenty of potential, however didn’t know methods to carry it. He performed all that ball and when he received older, some folks would ask, why ain’t he well-known? Properly, I’ll inform you why. It’s as a result of we didn’t know what to do. And while you don’t know what to do, you don’t know what to do. Possibly it simply wasn’t for him.”

It may very well be that straightforward. In 1980, Bobby Joe Douglas scored 54.0 factors per recreation for tiny Marion Excessive in north central Louisiana — rating No. 2 all-time, behind Finell. Douglas performed school ball at Northeast Louisiana College (now Louisiana-Monroe) and kicked across the outdated Continental Basketball Affiliation for a bit as a professional. Now 62, Douglas, a minister, says all of it bluntly: “Truthfully, I don’t suppose folks have a clue how arduous it’s to make it. When folks ask me, I simply inform ’em, ‘Man, I wasn’t ok!’”

When buddies and fellow gamers would point out Sports activities Illustrated or the 79-point recreation, Finell would chuckle it off, the best way outdated guys do. These have been the times. He was embarrassed, Daryl says, throughout his first few years again in New York.

Time, although, has a approach of fixing issues. As years handed, Finell got here to understand having these outdated days. He knew all too nicely what the probably various would have been if, as a youthful man, he’d stayed at Julia Richman, stayed in New York, stayed doing what he was doing. That may’ve been the true vanishing act.

Not everybody will get to say they went and did one thing. Finell, his buddies say, got here to know that.

In Charleston, in the meantime, those that witnessed Finell do what he did have been all the time left questioning the place the comet went. Contacted for a narrative 37 years after teaching him, Ronnie Gadsden stated he’d all the time thought Finell performed professional ball abroad earlier than dying younger. Previous Charleston sportswriters all voiced curiosity, with Charles Twardy, previously of The State, writing in an electronic mail: “I used to be simply occupied with that project lately and questioned what may need occurred to (him)?” Oronde Gadsden thought on it and stated: “He ended up going again to New York and taking part in at a small college or one thing, proper?” Howie Comen knew Finell had died, however didn’t know the way. He by no means might discover an obituary.

“For folks to not know what occurred to him,” Comen says, “appears like an injustice.”

Finell received older and took a job as a doorman and porter at 2 Horatio Road, a high-end, 17-story co-op overlooking the West Village. He liked the job, liked the folks. His greatest buddy and co-worker, Mike Delfish, remembers him carrying on with tenants, all the time telling tales and cracking jokes.

“None of them knew of him as a ballplayer,” he says. “To them, he was only a actually pleasant man.”

Delfish works at 2 Horatio to today. In his locker, there’s an outdated shiny image of Finell thumbed to the wall with Scotch tape. He was godfather to Delfish’s youngest son, Marquise.

After a failed relationship, Finell moved again in along with his mom someday within the late ’90s. He helped her by some well being points, however had one rule — no physician’s appointments on Mondays. That was his time off, his day to get again to the park.

In December 2000, on the day earlier than Christmas, Daryl and Finell performed video video games at their mother’s place, speaking their typical trash. Daryl, then a university scholar at Delaware State, was dwelling on break. Each he and Jackie have been there when Finell suffered a seizure that resulted in him being positioned on life help.

Finell Demetrios White died two days later at 31. He was mourned in New York and buried in Charleston. Tenants from 2 Horatio handed envelopes of money — what would’ve been Finell’s vacation bonuses, plus extra — to assist the household pay for the bills. Many attended the funeral in New York completely unaware of Finell’s highschool heroics.

“Everybody was there for a similar purpose,” Daryl says. “As a result of he had a very good coronary heart.”

Somebody like that deserves to have his story advised.

That’s actually how Jackie White and Mary Lee “Mae Mae” Rhodes see it. At this time, down in Charleston, inside that home on Cypress Road, they sit surrounded by footage of the boy they bear in mind. Some are cracked and curling, others in frames, well-preserved. In spite of everything this time, and after hours and hours speaking to a stranger, laughing and crying, they will’t fairly consider any of this.

That there’s this file on the market on the web. That the identify atop the listing is the one they thought everybody forgot about.

And that now Finell may be remembered, simply in case anybody goes looking out.

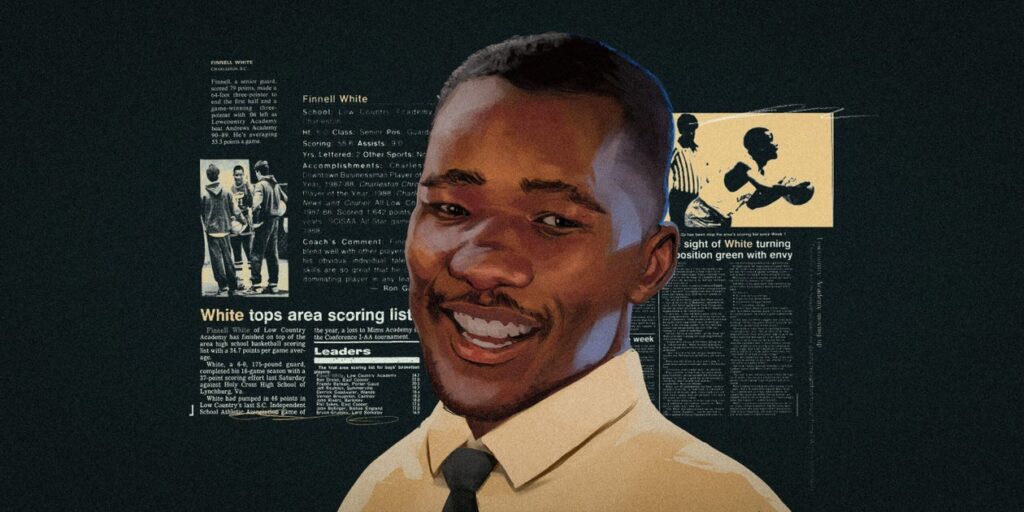

(Illustration: Oboh Moses for The Athletic; photographs: Brendan Quinn / The Athletic, Courtesy of the White household)