The brilliant lights would come quickly sufficient. On that Might evening in 1970, on the outdated ballpark on the confluence of the Des Moines and the Raccoon Rivers, they have been dimmer than the lights within the massive leagues. Tony La Russa knew that a lot, as a result of he’d been there.

La Russa was destined for a storied profession as a significant league supervisor, however on the sphere he was a bonus child who couldn’t actually hit. Taking part in for the Iowa Oaks, after a number of trials within the majors, matched his expertise stage. The Iowa pitcher that evening was far past it. He struck out 14 Evansville batters in 9 innings and even had two hits on the plate.

“There are minor leaguers, there are massive leaguers, after which there’s that greater league of All-Stars and Corridor of Famers,” La Russa, 78, stated by cellphone on Monday. “And that was Vida, and he was 20 years outdated.”

By the top of that 1970 season, within the majors for good with the Oakland Athletics, Vida Blue would throw a no-hitter. His subsequent season could be a baseball comet, a marvel in each majesty and brevity, the form of yr individuals speak about eternally, particularly in moments of loss.

Blue died at age 73 on Saturday, one other pillar gone from the one franchise moreover the Yankees to win three consecutive titles. Final month he visited the positioning of his former glory — the doomed and decaying Coliseum in Oakland, Calif. — for a celebration of the 1973 champs, the center of three A’s groups that gained the World Collection. Blue shuffled slowly to the diamond, his left hand clutching the elbow of an aide, his proper holding a protracted, wood cane.

“He appeared actually, actually frail, strolling round with a giant pole,” Mike Norris, a former Oakland teammate, stated by cellphone on Monday. “It was unhappy to see. He informed me he was worn out from chemo, he was weak, it was fairly painful and all that. We’re each Christians, so we simply stored praying for each other. And yesterday was it.”

The information of Blue’s dying reached his former catcher, Dave Duncan, late Sunday afternoon in Tucson, Ariz. Duncan, 77, was tending to his grandchildren however paused for a second to share what he noticed from behind the plate in 1971.

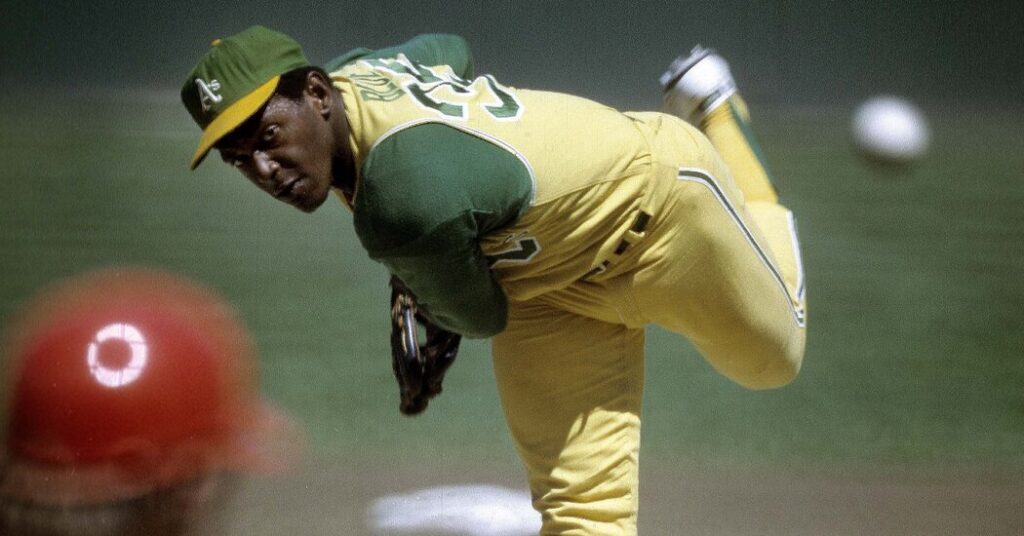

The left-handed Blue went 24-8 with a 1.82 E.R.A. that season, spinning 24 full video games and eight shutouts and dealing 312 innings, essentially the most in practically 60 years by a pitcher in his first full season. He gained the American League’s Most Helpful Participant Award and the Cy Younger, and there was nothing delicate about it.

“If he threw 120 pitches, 115 of them have been fastballs,” stated Duncan, a longtime pitching coach after his taking part in profession. “He rarely threw a curveball and didn’t have a changeup. He had nice management of it — he’d put it proper on the arms of right-handers and proper on the arms of left-handers — and he didn’t miss. He was wonderful.”

The 1971 season was staggering then, incomprehensible now. Blue misplaced his first begin after which gained eight in a row, all full video games. From June 1 via July 21, he averaged greater than 9 innings in a stretch of 11 begins (twice he went 11 innings).

In his subsequent begin, on three days’ relaxation, Blue bought a break: With followers jamming each nook of Tiger Stadium in Detroit, the place he’d gained the All-Star Sport earlier that month, Blue labored solely six innings. He gave up one hit and no earned runs, enhancing to 19-3 with a 1.37 E.R.A.

“He was magnetic,” stated La Russa, who watched from the bench that day. “His fame unfold so rapidly, and he was so dynamic, that folks began coming simply to observe him — and he delivered. It was a circus. It was like Mark McGwire, as a hitter, in ’98 and ’99.”

Buck Martinez, a former catcher, struck out all thrice he confronted Blue in 1971, and 15 occasions total, his most in opposition to any pitcher in a 17-year profession. Martinez does keep in mind an occasional curve amid the livid fastballs — “You possibly can hear it spin, it was so tight,” he stated — and the whirl of pleasure that adopted Blue in every single place.

“He was significantly better than Mark Fidrych, however he drew the identical consideration because the Chook did in ’76,” Martinez stated, utilizing Fidrych’s nickname. “All people wished to see Vida pitch, even when he was gonna stick it to you.”

Blue was a nationwide sensation. On the highway, his begins have been the highest-attended non-opening day video games for six A.L. groups: Baltimore, Boston, Detroit, Kansas Metropolis, the Washington Senators and the Angels. On the Coliseum, his 20 begins accounted for 40 % of the season attendance.

It was a occurring, and Blue, simply 22 years outdated, had all of the markings of crossover stardom: a Time journal cowl, a name-drop on “The Brady Bunch,” a spot on Bob Hope’s goodwill tour to army bases in South Vietnam; Okinawa, Japan; Thailand; and past. His contract talks with Charlie O. Finley, the A’s penurious proprietor, made for comedy fodder.

Blue: “Mr. Finley is a really persuasive man. He identified that I used just one arm final season.”

Hope: “So that you’ll signal the identical contract for subsequent yr? You’ll pitch for a similar cash?”

Blue: “Certain. Proper-handed.”

Blue really was a switch-hitter, and stays the reply to one of many nice trivia questions: who was the final switch-hitter to win American League M.V.P.? He was not a lot of a hitter (.104 for his profession) however carried himself with unusual athletic grace.

“It was like watching Bo Jackson stroll onto the baseball area, or Mike Trout,” stated Martinez, a longtime broadcaster. “I used to be 10 years outdated when Willie Mays walked onto Seals Stadium for the primary time and I used to be like, ‘Wow, that’s Willie Mays.’ You possibly can inform. You didn’t need to see him do something, and also you didn’t need to see his quantity. However you knew that was Willie Mays. Similar with Vida Blue.”

Rising up in Louisiana, Blue’s ardour was soccer: He wore No. 32 for Jim Brown, idolized Johnny Unitas and reveled in doing all of it — quarterback, cornerback, punts, kick returns. He turned down a soccer scholarship to the College of Houston after the dying of his father, Vida Sr., a steelworker.

Blue, the oldest of six kids, grew to become the household supplier. He bought a $25,000 bonus from the A’s, however he struggled to extract way more from Finley. He later turned down $2,000 from Finley to vary his first identify to “True,” as in True Blue — the identify he shared together with his father mattered a lot to Blue that finally he wore VIDA on his again.

It was all a part of Blue’s model, an interesting bundle of expertise and aptitude that impressed future ace left-handers: a gangly child from Livermore Excessive in California named Randy Johnson, and a person from Vallejo, Calif., named Carsten Charles Sabathia Sr., whose son, C.C., grew to become a member of the Black Aces.

The longtime pitcher Jim “Mudcat” Grant used that time period because the title of his 2006 e-book celebrating all of the Black pitchers with 20 wins in a season. There are 15 such pitchers, with Sabathia (in 2010) and one other left-hander, David Worth (2012), as the newest members.

Black participation within the majors has dwindled since Blue’s period, with rising prices for amateurs, restricted availability of school scholarships and the great depth in worldwide expertise. Norris, 68, who joined the membership in 1980, stated Blue’s dying was a reminder of what the game is lacking.

“The Black pitchers had extra swag than everyone else,” Norris stated. “I took satisfaction in that. It’s an perspective, man, stroll on the market such as you’re the best. The opposing workforce is like animals — they odor worry, and also you fight that with your personal ego.

“That’s all it’s, it’s ego. And that’s one factor Vida can take to the grave: He was one of many best.”