The summer time duel between Aaron Decide and Bobby Witt Jr. for the AL MVP is harking back to a traditional of the style.

On one facet, a ferocious slugger vying for the Triple Crown, main the league in OPS and flirting with 60 homers. On the opposite, a transcendent five-tool star hitting 30 homers, stealing 30 bases, and taking part in exemplary protection in the midst of the diamond.

It might be straightforward, at first look, to see a parallel to 2012, when Triple Crown winner Miguel Cabrera of the Tigers edged the Angels’ Mike Trout.

However the comparability comes with one downside:

Cabrera vs. Trout was a handy proxy battle for old skool vs. new college — the traditional masher in opposition to the younger king of WAR (Trout had important leads in each variations of wins above alternative). But for a lot of the summer time, Decide has performed the position of Cabrera and Trout, chasing a Triple Crown whereas hurtling towards 10.0 WAR and past.

As of Sunday, Decide led Witt in Baseball-Reference WAR (bWAR, 9.6 to 9.1) and FanGraphs WAR (fWAR, 9.8 to 9.7). The margins are slim when contemplating the variance of the wins above alternative metric, but when paired along with his offensive fireworks and pursuit of 60 house runs, Decide is a heavy favourite within the betting markets and a digital lock to take house his second MVP in three seasons.

The considerably muted conversations over Decide vs. Witt — in addition to Shohei Ohtani vs. Francisco Lindor within the Nationwide League — have illustrated a current shift in Most Useful Participant voting, performed annually by the Baseball Writers Affiliation of America.

If Decide is topped AL MVP, it should doubtless be the sixth time in seven years that the award goes to a place participant with probably the most Baseball-Reference WAR. (It is also the fifth time in seven years that the AL MVP is the chief in fWAR.)

Twelve years after Cabrera vs. Trout, the voting tendencies underscore an intriguing relationship between WAR and the MVP Award: Baseball writers have by no means been extra educated on the deserves, flaws and limitations of wins above alternative, a complicated metric with a number of types that has revolutionized how the game views total worth. And but, they’ve additionally by no means been extra more likely to choose an MVP who sits atop the WAR leaderboards.

In some methods, the connection is easy sufficient: Gone are the times when MVPs gained on the backs of RBI totals and puffed-up narratives. The appearance of WAR provided a framework for worth that has produced a better and extra knowledgeable citizens. However because the MVP aligns nearer and nearer with the WAR leaderboards, it’s straightforward to marvel: Have MVP voters, within the combination, grow to be too assured in WAR’s capability to find out total worth?

“In the event you’re a voter in a season like this and all you do earlier than you solid your poll is kind our leaderboards and seize the title on the high, I don’t suppose you’re doing all your diligence,” Meg Rowley, the FanGraphs managing editor, mentioned in an e mail. “First, that method assumes a precision that WAR doesn’t have.”

Decide and Ohtani — who, in his first 12 months within the NL, might be the primary participant with 50 homers and 50 stolen bases — each possess leads in bWAR which might be properly throughout the stat’s margin of error. (Lindor leads Ohtani in fWAR 7.4 to six.9.)

“Nobody ought to view a half a win distinction as definitive as to who was extra priceless,” Sean Forman, the founding father of Baseball-Reference, mentioned in an e mail.

For Don A. Moore, a researcher who research biases in human decision-making, the prominence of WAR in the case of voting may signify an instance of “overprecision bias,” which is characterised by the extreme certainty that one is aware of the reality.

“Human judgment tends to scale back the complexity of the world by zeroing in on a favourite measure or an interpretation or an explanatory concept,” says Moore, a psychologist and professor on the Haas Faculty of Enterprise at UC Berkeley. “That leads us, so simply, to neglect the uncertainty and variability and imprecision.”

Moore’s focus is within the space of “overconfidence.” He’s additionally a considerably informal baseball fan with a gentle spot for the “Moneyball” story.

“On the one hand,” he says, “it’s nice if obscure, subjective, doubtlessly biased impressions might be clarified and improved by quantification.”

On this method, the event and acceptance of WAR stands as a overcome the decision-making that dominated MVP voting for many years. However for an educational who sees overconfidence all over the place, his work additionally proffers a warning:

“It’s straightforward for us to zero in on some statistic and overlook that it’s imprecise and noisy and there are different approaches,” Moore says. “So overprecision leads all of us to be too positive that we’re proper and ask ourselves too little: What else may be proper?”

The story of wins above alternative is admittedly the story of baseball within the twenty first century. So let’s do the brief model: It started, roughly talking, within the early Nineteen Eighties with two pioneers of the sabermetric motion: Invoice James and Pete Palmer.

James, the godfather of sabermetrics, was, at that time, using a primitive idea of “alternative stage” to rank gamers in his annual “Invoice James Baseball Summary.” Palmer, in the meantime, had launched the system of “linear weights,” which decided an offensive participant’s worth in “runs” in comparison with a baseline common. By the Nineteen Nineties, Keith Woolner constructed on the work and developed worth over alternative participant, or VORP, which was acquired and promoted by Baseball Prospectus. With the essential concepts in place, the refinement, innovation and enchancment continued for one more 15 years.

What emerged was a consensus: an all-encompassing metric that measured a participant’s offense, protection and base operating in “runs above alternative” after which transformed that quantity into wins: WAR.

There was no official method, which meant that websites equivalent to Baseball Prospectus, Baseball-Reference and FanGraphs had been free to develop their very own variations. The crude nature of metrics for defensive and base operating meant that WAR was typically noisy in small samples. However the statistic introduced an answer for one in every of baseball’s everlasting issues.

“If you wish to correctly worth protection, it’s laborious to know the way to try this until you may have a framework,” says Eno Sarris, a baseball author at The Athletic and a previous MVP voter. “How do I examine a shortstop who’s 40 % higher than league common with the follow a DH who’s 70 % higher than league common with the stick? And not using a framework, it’s guesswork.”

FanGraphs started publishing its WAR statistic on its web site in December 2008, whereas Baseball-Reference unveiled its personal WAR variation for the 2009 season (earlier than a serious overhaul in 2012). The metric’s public arrival provided greater than only a higher mousetrap. Each websites may retroactively calculate WAR for previous seasons, which meant that previous MVP votes had been topic to historic peer evaluation.

Willie Mays, for example, led the Nationwide League in bWAR 10 instances, typically by important margins. He gained simply two MVP awards.

“That looks as if it’s backwards,” Sarris says.

In 1984, Ryne Sandberg gained the MVP award, and likewise led the league in WAR. (Charlie Bennett / Related Press)

To look again on the MVP votes of the previous is to see a snapshot of what the game valued at a given second — and a lot of shocking (and sometimes contradictory) tendencies. Whether or not it was the Reds’ Joe Morgan within the Nineteen Seventies, Robin Yount in 1982, Cal Ripken Jr. in 1983 or Ryne Sandberg in 1984, baseball writers typically did reward gamers with versatile talent units who led the league in bWAR (if anybody would have identified how one can calculate it). In addition they gave the award to aid pitchers 3 times from 1981 to 1992, whereas one of the vital predictive stats for MVP Award winners was RBIs. From 1956 to 1989, the RBIs chief gained the MVP 50 % of the time within the NL and 47 % of the time within the AL. (Since 1999, the NL RBIs chief has gained the MVP simply eight % of the time whereas the AL RBIs chief has gained the award 24 % of the time.)

“It was very completely different,” says Larry Stone, a longtime columnist on the Seattle Occasions who began overlaying baseball in 1987. “I’m virtually — not ashamed — however embarrassed. I feel I simply seemed on the counting stats primarily — house runs, common and RBIs had been large. And infrequently the tie-breaker was the group’s efficiency. There was not a lot sophistication again in these days.”

In fact, it was additionally true that generally the MVP was blatantly apparent it doesn’t matter what statistics had been used. When Barry Bonds gained 4 straight MVPs within the early 2000s, he led the league in bWAR every time. When Albert Pujols broke Bonds’ streak in 2005, he, too, led the league in bWAR. As supporters of WAR typically level out: The essential offensive numbers within the method are the identical ones we now have measured for the final century.

The info on MVP voting, nonetheless, began to shift within the 2000s as WAR entered the general public sq.. Noticing the tendencies, a baseball fan named Ezra Jacobson launched into a mission final winter to analysis the yearly distinction between every league’s chief in bWAR and its MVP. Not surprisingly, he discovered the typical had been shrinking for many years. Within the Nineteen Eighties and 90s, the typical distinction between the AL MVP and the chief in bWAR was 2.1 and three.04 WAR, respectively. Within the 2010s, the distinction had dwindled to 0.9. Within the 2020s, it’s 0.05.

Voters have grow to be extra knowledgeable and more and more formulaic and uniform.

“I feel the voting is massively improved from the place it was,” says Anthony DiComo, who covers the Mets for MLB.com and has been an NL MVP voter. “Present me the MVP voting in current historical past that was flawed? There have been some you would argue both method.

“In the event you go into the way in which previous, there’s fairly a number of in historical past the place you’ll be able to say: ‘Geez, they obtained it flawed. This man mustn’t have been MVP.’ And I don’t suppose that basically occurs that a lot anymore.”

The voting citizens consists of two BBWAA members from every American League and Nationwide League metropolis, creating a complete of 30 writers for every league award. When Stone obtained his first poll within the early Nineteen Nineties, the letter included an inventory of 5 guidelines that had been on the poll since 1931.

Voters had been instructed to contemplate:

- Precise worth of a participant to his group, that’s, power of offense and protection.

- Variety of video games performed.

- Basic character, disposition, loyalty and energy.

- Former winners are eligible.

- Members of the committee might vote for multiple member of a group.

If there was consternation over the foundations, it often got here again to No. 1.

“The phrase ‘worth’ is the one you ponder,” Stone says.

For many years, the obscure nature of “worth” allowed MVP voters to advertise a number of various meanings. (Go away it to a bunch of writers to fuss over language.) Did an MVP have to come back from a profitable group? Or was the worth really in serving to a group defy expectations? In 1996, the Rangers’ Juan Gonzalez gained the AL MVP over Ken Griffey Jr. and Alex Rodriguez regardless of being value simply 3.8 bWAR — or greater than 5.0 WAR lower than Griffey and Rodriguez. This was, partly, as a result of the Mariners teammates break up a few of the vote. However it was largely as a result of Gonzales helped the Rangers make the playoffs for the primary time in franchise historical past.

“Within the 90s,” mentioned Tyler Kepner, a veteran baseball author at The Athletic, “it at all times gave the impression to be: ‘Who was the perfect participant on the group that appeared least more likely to win getting into?’ ”

When Bob Dutton, a former baseball author at The Kansas Metropolis Star, grew to become nationwide president of the BBWAA within the late 2000s, he took on a analysis mission to verify the unique intent of the phrase “worth.” “It was at all times purported to imply ‘the perfect participant,’ ” he says.

WAR introduced a framework for contemplating gamers of their totality. As a consequence, it has brought on a technology of youthful writers and voters to reframe the thought of worth, separating it from group success. WAR has not simply grow to be a metric for figuring out worth; it’s grow to be synonymous with the thought. The evolution doubtless helped pitchers Justin Verlander and Clayton Kershaw win MVP Awards in 2011 and 2014, respectively: each pitchers led their leagues in WAR.

“It displays the instances we’re in,” Kepner mentioned. “As entrance places of work and the sport itself values knowledge increasingly more, it stands to motive that the voting would mirror that as properly.”

Anecdotally, it’s practically unattainable to search out an MVP voter who blindly submits a poll copy and pasted from a WAR leaderboard. Contemplating there are a number of variations, that might be tough. Rowley, the managing editor of FanGraphs, and Forman, the founding father of Baseball-Reference, each emphasize that WAR must be a place to begin in figuring out the MVP — not the end line.

DiComo, a previous voter, begins the method by compiling a spreadsheet with the highest 10 in a lot of statistics: weighted runs created plus, anticipated weighted on-base common, bWAR, fWAR, and win likelihood added. Step one creates a small pool of candidates. He dietary supplements that with conversations with gamers, executives, managers and different writers. Then he would possibly use different numbers as he ranks the highest 10 on his poll.

The aim, he mentioned, is “to tease out a whole lot of my very own biases that may exist with out even realizing it.”

(Full disclosure: I voted for AL MVP in 2016 and 2017 and used a course of roughly just like this one.)

If there’s one important distinction within the voting course of 30 years in the past — past the knowledge out there — Stone notes that it was “extra of a solitary train, which meant you couldn’t be influenced.” Not solely are the WAR leaderboards public and up to date every day, however particular person MVP ballots are publicly launched on the web.

“I do fear about groupthink,” Stone says.

“My argument,” DiComo says, “is that we’ve gotten so good at measuring this, and voters have a tendency to consider it increasingly more equally. So it’s like: ‘Yeah, if there’s a small edge, in actuality there’s an enormous edge in voting as a result of everyone seems to be seeing that small edge and voting for the man who has it.’”

WAR has not remained static through the years; FanGraphs now makes use of Statcast’s defensive metrics of their WAR method. Nonetheless, whereas defensive metrics have improved considerably from the early 2000s, they’re nonetheless based mostly on a pattern of performs drastically smaller than, say, 700 plate appearances. Whilst WAR improves and turns into ever extra relied on, it stays solely a partial measure.

Brown, the professor at UC-Berkeley, likened the failings of WAR to economists utilizing gross home product, or GDP, to measure financial progress.

“All people is aware of it’s woefully imperfect for capturing what we really care about in the case of financial progress,” Brown mentioned of GDP. “However the factor is: It’s higher than the alternate options. So we find yourself counting on it very closely.”

The identical might be mentioned of WAR. It isn’t an ideal stat, however it’s the greatest we now have. Its creators and supporters are clear and specific in explaining {that a} half win (0.5 WAR) will not be statistically important in figuring out which participant had a extra priceless season. However the factor is: Small margins are sometimes determinative.

A decade later, the Trout-Cabrera MVP race might need gone slightly in a different way. (Harry How / Getty Pictures)

Each MVP winner for the final decade has completed inside 0.6 WAR of the league lead amongst place gamers at both Baseball-Reference or FanGraphs. The final MVP who didn’t: Miguel Cabrera in 2012.

Stone, who retired final 12 months, had a vote that season. Cabrera was the primary participant to guide the league in batting common, house runs and RBIs since 1967. However Trout was so dominant in WAR that Stone was torn.

“I agonized over that,” he mentioned. “I ended up voting for Cabrera, simply because I assumed the Triple Crown was such a monumental achievement.”

Cabrera obtained 22 of 28 first-place votes; Trout took the opposite six. However 12 years later, the winds have continued to vary. If the vote occurred at present, Stone believes the consequence may be completely different.

“I feel it may be nearer,” he mentioned. “I feel there’s an opportunity that Trout would possibly win.”

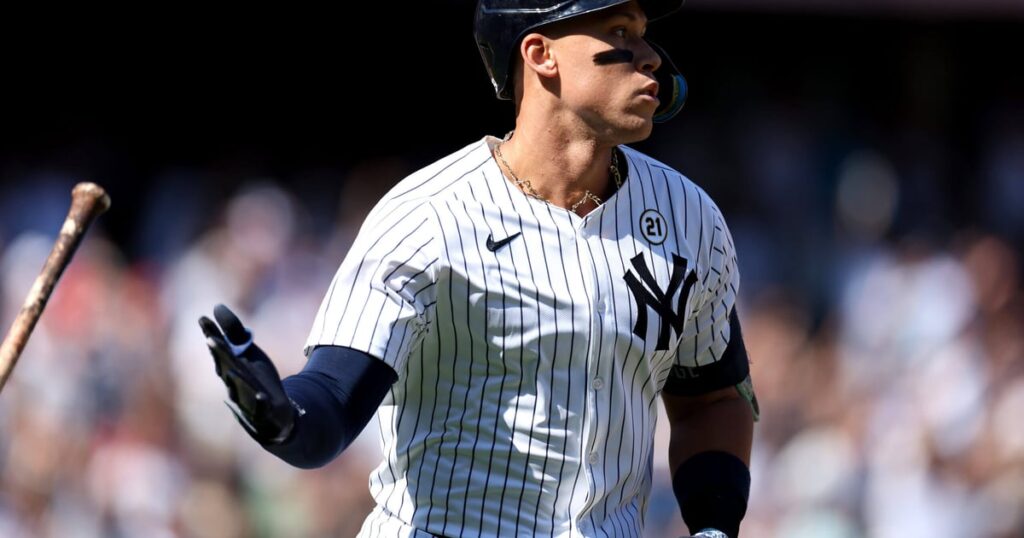

(High picture of Decide: Luke Hales / Getty Pictures)