Sarah Rainsford,Jap Europe correspondent

BBC

BBCAt 12 years outdated, Lera is studying to stroll once more. Timid steps at first, however extra assured with every one she takes.

Final summer time a Russian missile assault shattered one in every of her legs, and left the opposite badly burned.

Near 2,000 kids have been injured or killed in Ukraine since Vladimir Putin launched his full-scale invasion. However the struggle doesn’t at all times depart seen scars like those who run up Lera’s leg.

“Nearly each youngster has issues brought on by the struggle,” says psychologist Kateryna Bazyl. “We’re witnessing a catastrophic variety of kids turning to us with totally different disagreeable signs.”

Proper throughout Ukraine, younger persons are experiencing loss, concern and nervousness. An rising quantity battle to sleep, have panic assaults or flashbacks.

There’s additionally been a surge in instances of kid melancholy amongst a technology rising up below hearth.

Lera Vasilenko, 12, in Chernihiv, northern Ukraine

Lera noticed the missile that damage her seconds earlier than it hit.

It was a sizzling summer time vacation and the centre of Chernihiv was busy. She and her good friend, Kseniya, have been making an attempt to promote their selfmade jewelry to the passing crowd.

“I noticed one thing flying from as much as down. I assumed it was some form of airplane that will go up once more, nevertheless it was a missile,” Lera says, the phrases tumbling out at excessive pace like she doesn’t wish to dwell on their that means.

After the explosion, she ran backwards and forwards in panic on her mangled leg earlier than she realised she’d been injured.

“Folks say I used to be in a state of shock. It was solely when Kseniya stated, ‘Take a look at your leg!’ that I felt the ache. It was terrible.”

At first of all-out struggle in 2022, the bombardment of Chernihiv in northern Ukraine was fixed. However inside weeks, the Russian forces had been pushed again. Life slowly returned to the town.

Then, on 19 August 2023, the native theatre hosted an exhibition of drone producers, and Russia attacked. Shards of steel sliced via the streets throughout.

9 months later, Lera lifts her trouser leg to disclose a number of deep scars and a pores and skin graft. There’s a giant bump the place steel implants have been inserted.

The injuries are therapeutic effectively and she or he strikes nimbly on her crutches. However she nonetheless struggles with the sound of air raid sirens.

“If they are saying there’s a missile heading for Chernihiv then I am going loopy,” she admits. “It’s actually dangerous.”

She insists she’s coping, and hasn’t modified, however her sister isn’t so positive. “You’re extra explosive,” Irina tells her. Lera nods sheepishly. “I wasn’t so aggressive earlier than.”

It’s one in every of many reactions that youngster psychologists are seeing to the stresses of this struggle.

“Youngsters don’t perceive what’s occurred to them, or typically the feelings they really feel,” explains Iryna Lisovetska, from the Voices of Youngsters charity that’s serving to a whole bunch of younger Ukrainians throughout the nation.

“They’ll present aggression as a type of self-protection.”

For Lera, the struggle has been doubly merciless.

Just a few months earlier than she was injured, her brother was killed preventing on the entrance line. The 2 have been shut and Lera nonetheless struggles to just accept that Sasha has gone.

“I think about he’ll name at any second. I used to see his face in passers-by on the road. I nonetheless can’t consider it,” she confides quietly, wrapped in a Ukrainian flag she plans to take to Sasha’s grave. A alternative for one frayed by the wind.

With out warning, Irina faucets her cellphone and Sasha’s deep voice fills the room. “I actually love you,” the soldier assures his sisters in a final audio message despatched from the entrance.

It’s the primary time Lera’s heard his voice since he died. Her chin trembles with emotion.

Daniel Bazyl, 12, in Ivano-Frankivsk, western Ukraine

Daniel’s biggest concern is to expertise a loss, like Lera.

His father is a soldier, serving near their hometown of Kharkiv the place the preventing has intensified.

Russian troops not too long ago crossed the border in a shock offensive, taking new floor, as missile assaults on the town have elevated. Amongst these killed in simply the previous week was a 12-year-old woman, out procuring along with her dad and mom.

“Dad tells me it’s all okay, however I do know the scenario there’s not the very best,” Daniel says. “In fact I fear about him.”

The 12-year-old now lives in western Ukraine along with his Mum, a world away from Kharkiv. Russian missiles do attain Ivano-Frankivsk however you get much more warning. The streets are crowded and relaxed. There’s even site visitors jams.

However even right here, Daniel can’t escape the battle. He’s taped a prayer above his mattress which he recites every evening for his father’s security, although he was by no means spiritual earlier than.

He and his mum, Kateryna, have been refugees for some time. They returned to Ukraine as a result of she’s a baby psychologist and noticed the pressing want for her abilities.

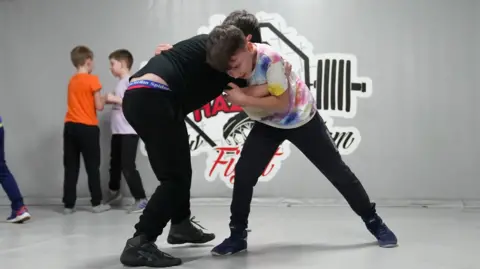

She does her greatest to maintain her personal son distracted with limitless actions: there’s a skate park and guitar courses. He went busking to boost cash for the Ukrainian army and there’s a combat membership to assist him stand as much as the college bullies.

“I attempted to seek out issues he beloved earlier than, to proceed doing right here, and it really works,” Kateryna says.

However the boy from the north east nonetheless struggles to slot in.

“It actually bothers me when there’s an air raid at college and everybody’s comfortable they’ll miss class,” Daniel says. “Right here, a siren simply means going to the bunker. However it really means there’s preventing elsewhere in Ukraine.”

Daniel counts the hours between on-line calls along with his dad. His father has been sending parcels stuffed with artwork supplies in order that he can train him to attract, remotely.

“I wish to consider the struggle will finish quickly,” Daniel shares his biggest need. That manner, he may go residence to Kharkiv, he says.

“And that will be actually cool.”

Angelina Prudkaya, 8, in Kharkiv, north-eastern Ukraine

Eight-year-old Angelina continues to be within the metropolis, dwelling in the midst of a bomb web site.

She’s from the Saltivka suburb, which is Daniel’s residence too. When Russian troops first superior within the area two years in the past, it was proper within the firing line and Angelina was sheltering along with her household of their basement.

“It was very scary. I simply thought, when will all of it finish? There have been rockets and a airplane flew over us,” the little woman remembers, tugging on the sleeves of her sweater.

In early March 2022, the large block of flats subsequent door was destroyed by a missile.

Angelina’s mum, Anya, informed her to dam her ears and lie quietly.

“I assumed we’d be buried beneath the ruins. That our constructing had been hit, and would collapse,” she says, eyes large on the reminiscence.

After that they fled.

However when Ukrainian forces liberated the northern area final 12 months, the household returned to Saltivka. They’re the one individuals dwelling of their block of flats, surrounded by smoke-blackened buildings and smashed glass. Regardless of the shrapnel holes within the kitchen wall, it’s residence.

Now Kharkiv is a nervous place once more. The glide-bomb assault on a DIY retailer final weekend was near Angelina’s flat.

Vladimir Putin says he has no plans to attempt to take the town however Ukrainians have realized by no means to belief him.

“After they begin to bomb, I inform mummy I’m going to the hall and she or he sits there subsequent to me,” Angelina says, with the calm of an excessive amount of expertise.

Transferring to the hall places an additional wall between your physique and any explosion. It’s minimal safety.

Angelina ought to have began at her native college by now, nevertheless it has a gap blown via the facet. She barely remembers kindergarten as a result of earlier than the invasion, there was Covid.

Anya tries to counter the solitude by taking her daughter to exercise periods, together with pet remedy. It’s run by the kids’s charity Unicef, underground on the metro for additional security.

Throwing balls for a shiny canine referred to as Petra, Angelina involves life in matches of giggles.

However when night falls over her residence, the lights don’t come on anymore. Russia has been concentrating on the ability provide.

So Angelina lights a candle, rigorously, her small determine casting an enormous shadow on the wall of their flat. “It occurs on a regular basis,” she shrugs, concerning the blackouts.

Like Lera and Daniel, Angelina is adapting to this struggle as greatest she will.

However throughout the nation, there’s rising demand for assist.

“We inform the kids it’s alright to really feel no matter they do,” Kateryna Bazyl explains. “We are saying we may also help them perceive find out how to management these feelings, to not destroy all the things round them. Or themselves.”

After I ponder whether there’s sufficient assist to go spherical, she pauses.

“To be trustworthy, we have now a extremely large queue.”

Manufacturing by Anastasia Levchenko and Hanna Tsyba

Pictures by Joyce Liu